Celebrating the Centennial

Compiled by Andrea Watters, Naval Aviation News editor, and Fred Flerlage, NAN Art Director.

During 2022, Naval Aviation celebrates the centennial of the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier.

During 2022, Naval Aviation celebrates the centennial of the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier.

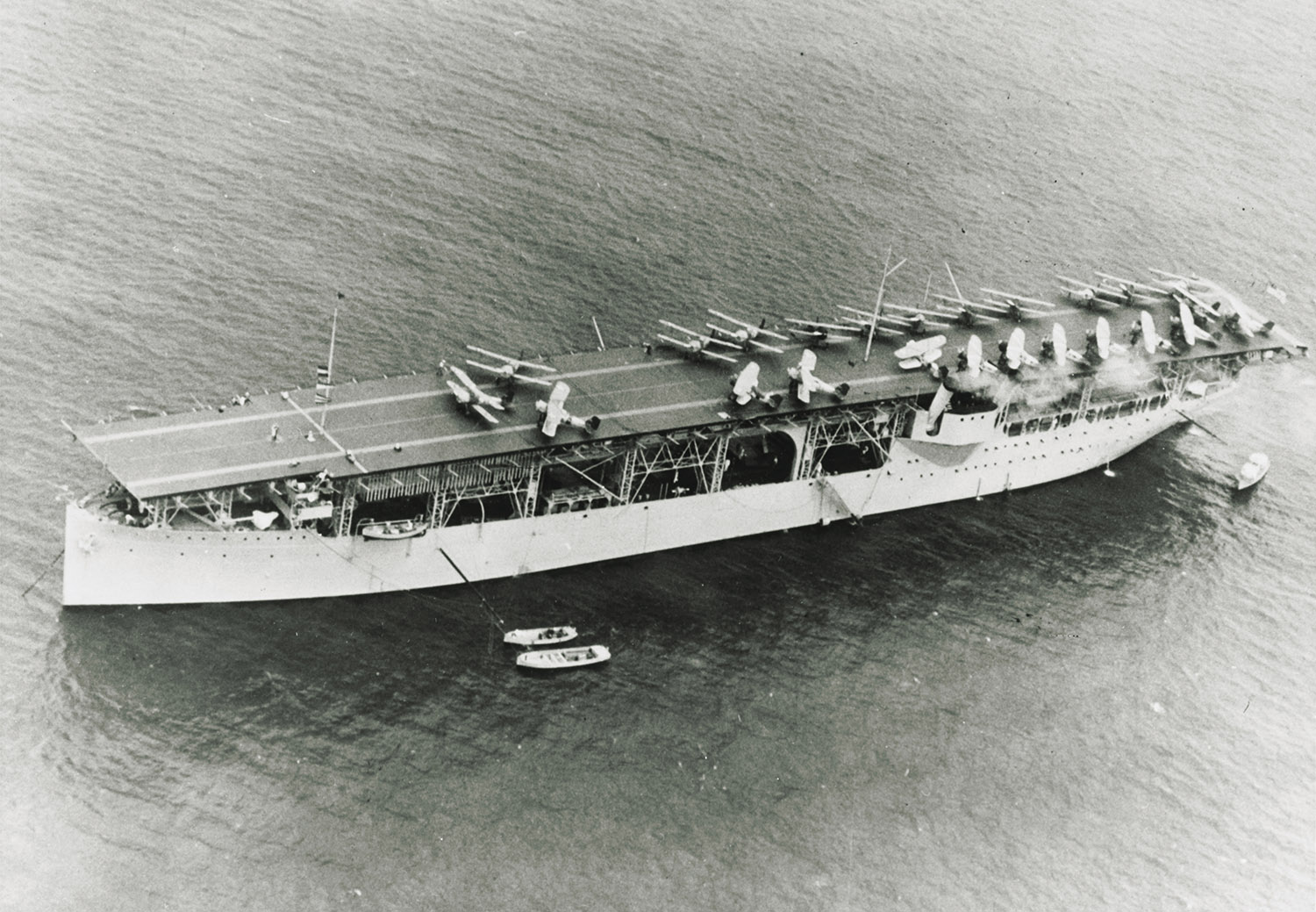

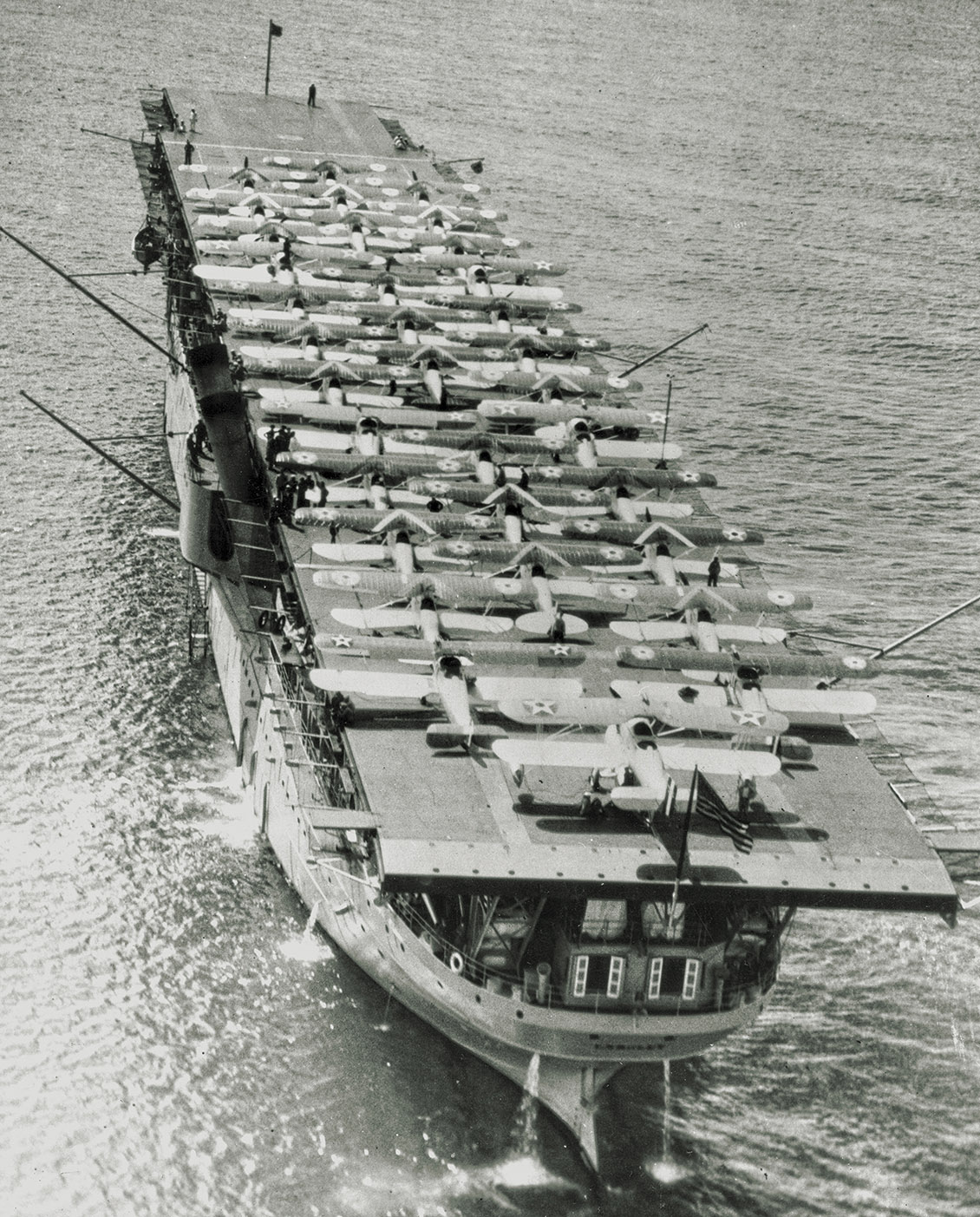

In March, a gala in Norfolk, Virginia, highlights the commissioning of the Navy’s first aircraft carrier, USS Langley (CV 1), 100 years ago. Originally constructed as a collier ship, USS Jupiter, was converted into an aircraft carrier beginning in 1920. She would serve from 1925-1936, primarily as a testing platform for the Navy to develop tactics, techniques and procedures for the landing of aircraft aboard ships. She was later converted to a seaplane tender during World War II.

According to former Naval Aviation News staff writer Scot MacDonald, “Small and gangling as she was, USS Langley was the first-born of a large fighting family of powerful Navy ships.” In this issue, the NAN revisits MacDonald’s 14-article series on the “Evolution of the Aircraft Carrier,” first published in 1962-1963.

We hope you enjoy this look back on Naval Aviation’s legacy of innovation that began with the Langley to create a history of dominance that continues with the Nimitz- and Gerald R. Ford-class carriers.

Evolution of the Aircraft Carriers: Langley, Lex and Sara

By Scot McDonald

Editor’s note: The following is a condensed reprint of the article from the May 1962 issue of Naval Aviation News.

“One day,” said Capt. Thomas T. Craven, who had relieved Capt. Noble E. Irwin as Director of Naval Aviation in May 1919, “one day, when someone suggested that shoveling coal was becoming unpopular, we proceeded to angle for the colliers Jupiter and Jason. Although some conservative seniors frowned on the plan, in time and with the Secretary of the Navy’s [SECNAV] approval, we persuaded Congressional committees of the wisdom of converting one ship, [USS] Jupiter, into an aircraft carrier. Having an entirely inadequate speed, the vessel could not possibly fulfill all service requirements, but she could serve as a laboratory for determining naval needs. Naval Aviation took heart.”

“One day,” said Capt. Thomas T. Craven, who had relieved Capt. Noble E. Irwin as Director of Naval Aviation in May 1919, “one day, when someone suggested that shoveling coal was becoming unpopular, we proceeded to angle for the colliers Jupiter and Jason. Although some conservative seniors frowned on the plan, in time and with the Secretary of the Navy’s [SECNAV] approval, we persuaded Congressional committees of the wisdom of converting one ship, [USS] Jupiter, into an aircraft carrier. Having an entirely inadequate speed, the vessel could not possibly fulfill all service requirements, but she could serve as a laboratory for determining naval needs. Naval Aviation took heart.”

At the end of World War I, Great Britain had the Hermes, Eagle and Argus in operation, while Germany successfully converted the merchantman Stuttgart into a carrier. Craven was in France at the time, assigned as aide for aviation to Commander, U.S. Naval Forces and Commander, Naval Aviation Forces. He was approached by the CNO—and later, by SECNAV Josephus Daniels—and asked to assume the Office of Director of Naval Aviation.

Returning to America, he immediately studied the problems of strengthening the Navy’s complement of pilots and support personnel, obtaining “apparatus suitable for their use,” and developing tactics.

Cmdr. Kenneth Whiting, in a memorandum to the Committee on Naval Affairs, sized up the situation: “When the sear ended those who had chosen the Navy as a life work, and especially those of the Navy who had taken up Naval Aviation, revived the question of ‘carriers’ and ‘fleet aviation.’ They found the sledding not quite so hard as formerly, but the going was still a bit rough.

“The naval officers who had not actually seen Naval Aviation working retained their ultra-conservatism; some of those who had seen it working were still conservative, but not ultra; they were in the class ‘from Missouri’ and wished to be ‘shown.’ Others, among the ranking officers who had seen, had conquered their conservatism, and were convinced.

“This latter group, headed by the General Board of the Navy, and including Adm. Henry T. Mayo, Adm. N.C. Twining, Capt. Ernest J. King and Capt. W.S. Pye, both on the staff of the commander in chief during the war, Capt. H.I. Cone and Capt. Thomas T. Craven, demanded that ‘carriers’ be added to our fleets.

“This latter group, headed by the General Board of the Navy, and including Adm. Henry T. Mayo, Adm. N.C. Twining, Capt. Ernest J. King and Capt. W.S. Pye, both on the staff of the commander in chief during the war, Capt. H.I. Cone and Capt. Thomas T. Craven, demanded that ‘carriers’ be added to our fleets.

“The net result of these demands was the recommendation that the collier Jupiter be converted into a carrier in order that the claims of the naval aviators might be given a demonstration.”

Jupiter did not possess all the characteristics that would have made her an ideal aircraft carrier, but she did have many advantages. Commissioned April 7, 1913, as fleet collier No. 3, she, with the Neptune, carried the first Naval Aviation detachments to France in World War I. At war’s end, she was scheduled for retirement.

“At the time she was selected [for conversion to an aircraft carrier],” Whiting pointed out, “her advantages outweighed her disadvantages.”

The ship was slow and might prove a drogue to a fast-moving fleet. But she did have the necessary length to permit planes to fly off from a specially prepared deck. Her hold spaces were very large, “with high head room in them, a difficult thing to find in any ship. She had larger hatches leading to these holds than most ships, a factor permitting the stowing of the largest number of planes.”

The ship was slow and might prove a drogue to a fast-moving fleet. But she did have the necessary length to permit planes to fly off from a specially prepared deck. Her hold spaces were very large, “with high head room in them, a difficult thing to find in any ship. She had larger hatches leading to these holds than most ships, a factor permitting the stowing of the largest number of planes.”

Jupiter was electrically driven. Her top speed was a comparatively slow 14 knots. One of the clinching arguments for her conversion was her small crew requirement. With hostilities over, non-regular Navy men were eager to continue civilian activities and were leaving service in large numbers.

Jupiter sailed to Norfolk Navy Yard where the conversion work was accomplished. “We thought she could be converted cheaply,” Whiting said, “—that was a mistake, however. In any event, she will have cost less when completely converted than any other ship we might have selected. We thought she could be converted quickly—that was another mistake. The war is over, and labor, contractors and material men are taking a breathing spell.

“The recommendation for her conversion was made by the General Board of the Navy early in 1919; Congress appropriated the money [on 11 July] 1919; she was promised for January 1921; she may be ready by July 1921.” She was not.

Jupiter’s designation was changed to CV on July 11, 1919; she went into the yard for conversion March 1920 and was commissioned USS Langley (CV 1) on March 20, 1922, at Norfolk.

In the yards, all the coal-handlin g gear was removed from the collier and a flight deck, 534 feet long and 64 feet wide, was installed. At first, it was planned that this deck would be completely free of obstruction, and so it was in the Langley.

g gear was removed from the collier and a flight deck, 534 feet long and 64 feet wide, was installed. At first, it was planned that this deck would be completely free of obstruction, and so it was in the Langley.

An elevator was installed to lift planes from the assembly and storage deck to the flight deck. A palisade was built around this elevator to provide a windbreak, protecting the planes and men while the aircraft were being assembled.

An elevator was installed to lift planes from the assembly and storage deck to the flight deck. A palisade was built around this elevator to provide a windbreak, protecting the planes and men while the aircraft were being assembled.

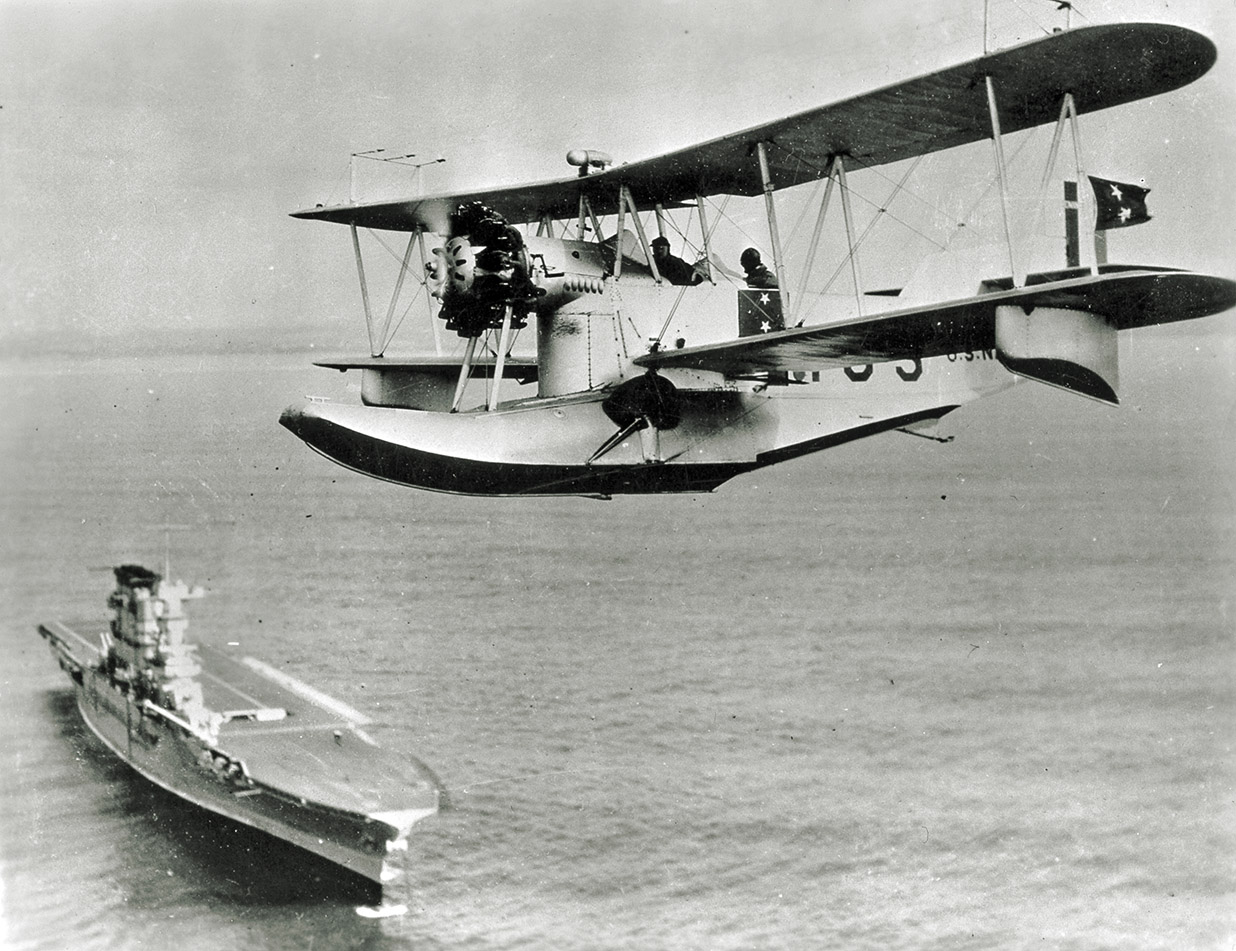

For the hoisting of seaplanes, two cranes with large outreach were installed on the hangar deck, one on either side of the ship. Traveling cranes were installed beneath the flight deck for hoisting planes from the hold and for transferring them fore and aft to the ship spaces and elevator.

The collier’s firerooms were located well aft. This permitted an easier handling of gasses to guarantee a minimum interference with planes when they touched down on her deck. She had ample space for machine, carpenter, metal and wing repair stowage; spare parts, spare engines, and shops; for gasoline and lubricating oil and aircraft ammunition. Her living quarters appeared to be a bit crowded, but sufficient for the work to be undertaken.

From May 1919 to March 1921, Craven directed much attention to the training of pilots. “Pending the completion of facilities that would enable the Navy to train pilots to fly landplanes from the deck of a carrier,” he wrote, “arrangements were effected to have naval flyers instructed in the Army school at Arcadia, Florida. The entire naval contingent[s] quickly and easily completed the Army’s course.” They also received Army training at Mitchel Field on Long Island and at Langley Field, Virginia.

From May 1919 to March 1921, Craven directed much attention to the training of pilots. “Pending the completion of facilities that would enable the Navy to train pilots to fly landplanes from the deck of a carrier,” he wrote, “arrangements were effected to have naval flyers instructed in the Army school at Arcadia, Florida. The entire naval contingent[s] quickly and easily completed the Army’s course.” They also received Army training at Mitchel Field on Long Island and at Langley Field, Virginia.

Earlier, Lt. Cmdr. Godfrey de Courcelles Chevalier led a team of 15 pilots who were put into training with landplanes, practicing touch-and-go flight deck landings on a 100-foot-long platform constructed on a coal barge at the Washington Navy Yard. The barge was moved to Anacostia where landing tests were conducted.

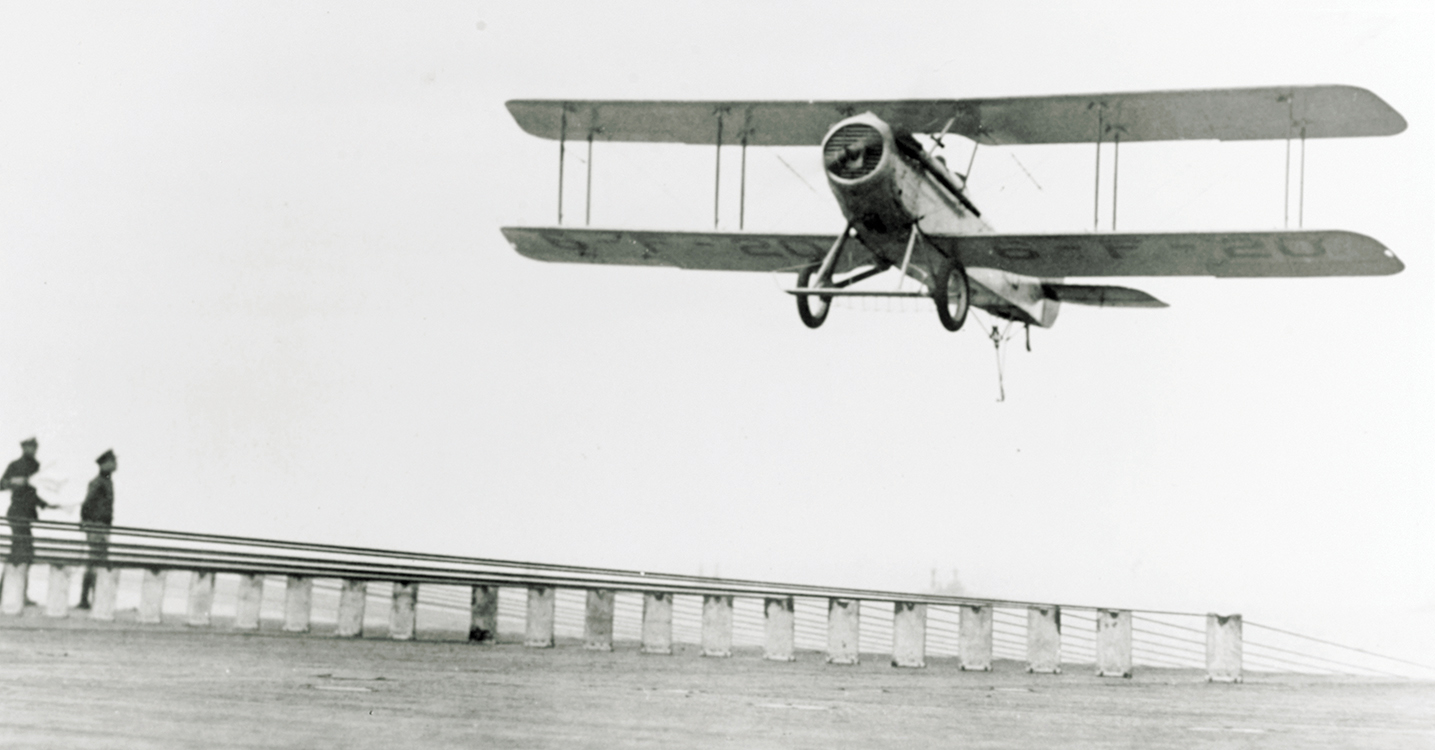

Experiments were conducted at Hampton Roads, Virginia, in which Lt. Alfred M. Pride participated. A turntable platform was used, similar to the type the British developed in WWI—in turn, an improvement of Ely’s arrangement used on the Pennsylvania. A Bureau of Aeronautics (BUAER) letter dated Nov. 19, 1923, described the Langley and British systems. The Langley gear, the letter states, “depends on an athwartship retarding force while the [British] gear depends on air resistance together with the resistance set up by fore and aft cables.” The Langley wires were suspended about 10 inches above the deck. They were not entirely satisfactory, but were used, with some modifications, in the Lexington and Saratoga until 1929.

When Langley eventually went to sea in September 1922, she had an arresting gear installed.

The first take-off from the deck of Langley was piloted Oct. 17, 1922, by Lt. Virgil C. Griffin in a VE-7-SF. On Oct. 6, the first landing was made by Chevalier in an Aeromarine aircraft while the ship was underway. He had contributed significantly to perfecting the arresting gear installed aboard—still in an experimental stage. His plane nosed over. Whiting, on Nov. 18, became the first to catapult from the deck of Langley; he flew a PT torpedo bomber.

The first take-off from the deck of Langley was piloted Oct. 17, 1922, by Lt. Virgil C. Griffin in a VE-7-SF. On Oct. 6, the first landing was made by Chevalier in an Aeromarine aircraft while the ship was underway. He had contributed significantly to perfecting the arresting gear installed aboard—still in an experimental stage. His plane nosed over. Whiting, on Nov. 18, became the first to catapult from the deck of Langley; he flew a PT torpedo bomber.

These aircraft—and other types used at the time—were of standard design. BUAER decided to delay introducing new types, although studies of planes built for carrier operations started with the conversion of the collier. Vought and Aeromarine service types were first to be modified for operations aboard; arresting hooks were installed, and the landing gear strengthened.

For the first three years following her commissioning, USS Langley had no regularly assigned squadrons. She was used as an experimental ship, testing gear and aircraft, and training pilots and support personnel. For the first five years of her operations, she was the only aircraft carrier in the U.S. Navy. Because of the flight deck installed, she was quickly dubbed “the Covered Wagon,” and this was reflected in her official insignia.

The principle purpose of Langley was to teach naval aviators about carrier operations, but the early days were certainly tough on pilots, according to “Our Flying Navy,” a book published in 1944.

“‘Instrument face’ was the distinguishing mark of Langley’s pilots, who loosened teeth and flattened noses against their instrument panels while negotiating the hazards of landing on Langley’s small flight deck and crude arresting gear. Planes went overboard, piled up in the crash barrier, stood on their noses and came apart. [There were few fatalities.] But the science of carrier operations was developed as a monument to these pilots’ perseverance.” The “small flight deck” was as long as later-day “baby flattops.”

Arresting gear and catapult systems were tried, modified, improved upon; pilots qualified for carrier landings and take-offs. In March 1925, Langley entered her first fleet exercise, Fleet Problem No. 5, off the lower coast of California. Scouting flights from the carrier now became standard procedure and so impressed official observers that they recommended the completion of USS Saratoga and USS Lexington be speeded up.

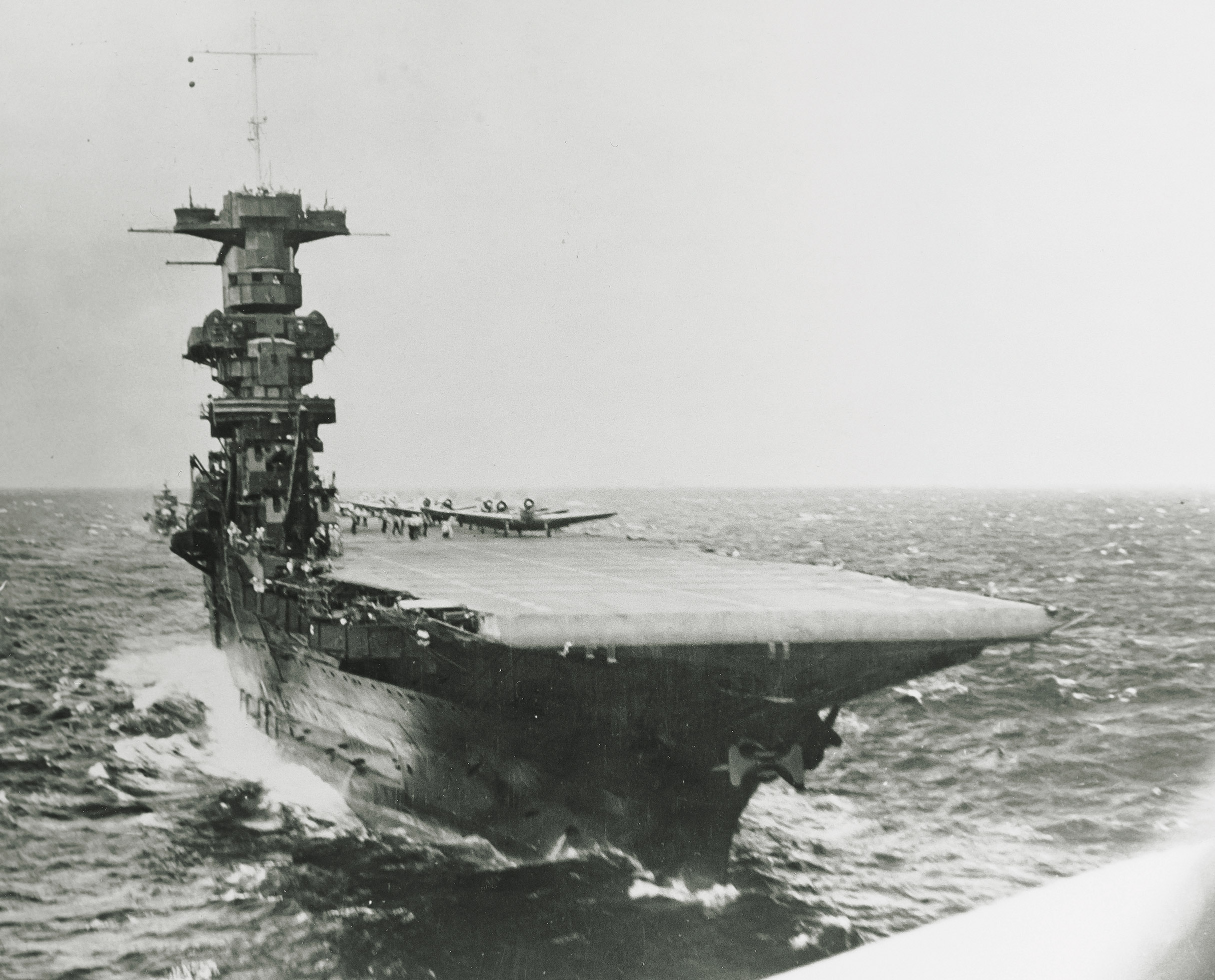

There was an urgency related to these tests. Already in the ways were the keels of two battle cruisers destined for the scrap heap as a result of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. A clause within this treaty permitted their conversion to aircraft carriers. Tests aboard Langley were to influence greatly the final designs of the two ships under conversion. These converted battle cruisers were to become USS Lexington (CV 2) and USS Saratoga (CV 3).

Before Langley was commissioned, Craven became Commandant of the Ninth Naval District, and was relieved March 7, 1921, by Capt. William A. Moffett, who became the last Director of Naval Aviation. On July 26, 1921, that office was abolished, replaced by the newly authorized Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, which Moffett assumed.

For the full article and series, visit:

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/naval-aviation-history/evolution-aircraft-carriers.html