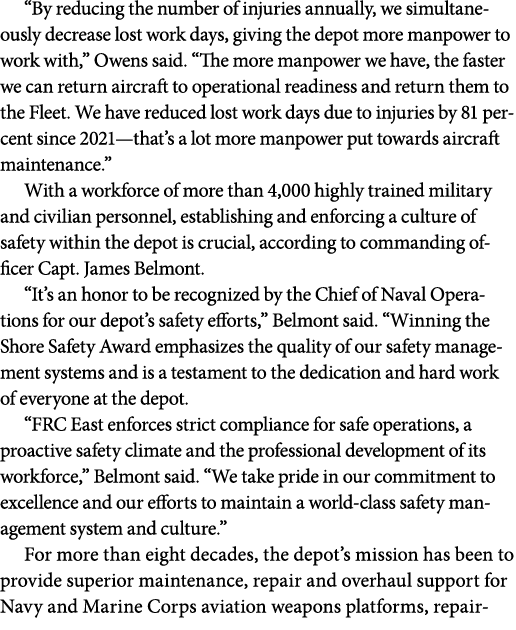

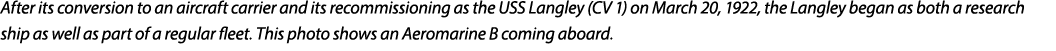

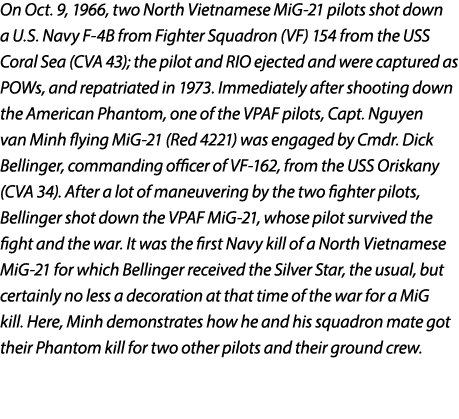

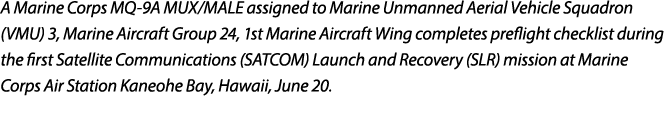

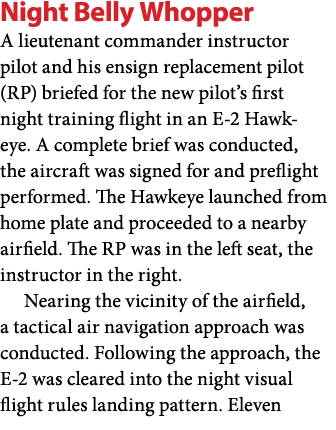

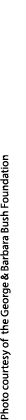

America’s First Aircraft Carrier, USS Langley and the Dawn of U.S. Naval Aviation

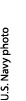

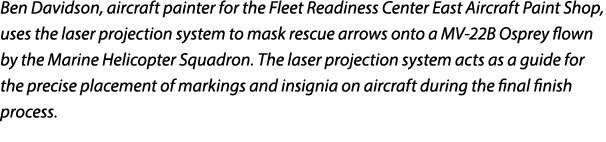

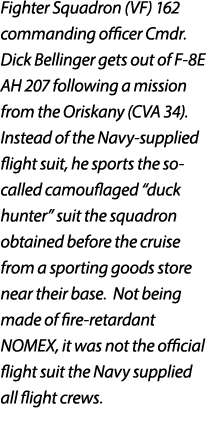

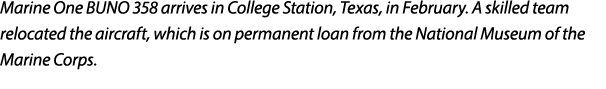

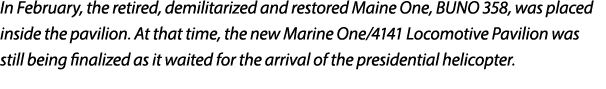

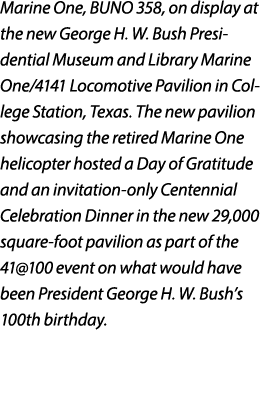

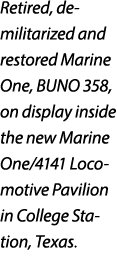

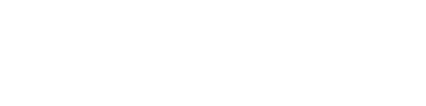

By David F. Winkler, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. 2024. 284 pp. Ill.

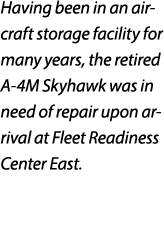

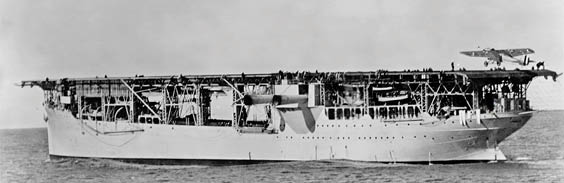

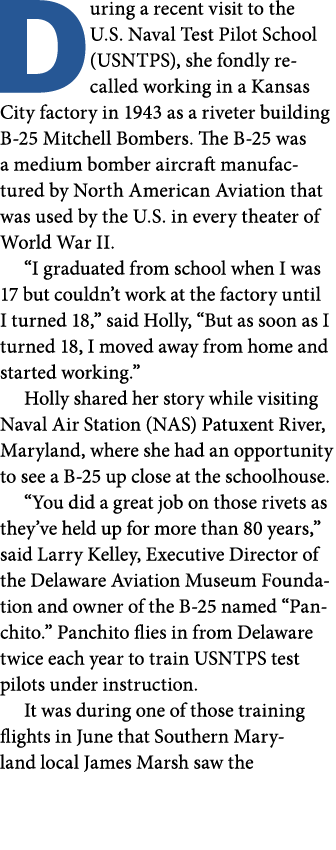

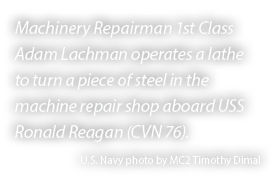

This heavily researched history of the first American aircraft carrier might be considered the story of two entirely different ships that began in the first years of the 20th century, as America seriously developed a fleet of ocean-going battleships and assorted other ships—most notably 1907’s, “The Great White Fleet” of President Theodore Roosevelt.

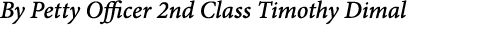

Great Britain was involved with beginning a totally new class of capital ships, one that would operate a newcomer to the world’s arsenal—the airplane, just in time for what was, indeed, the First World War.

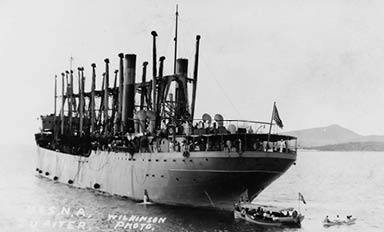

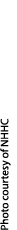

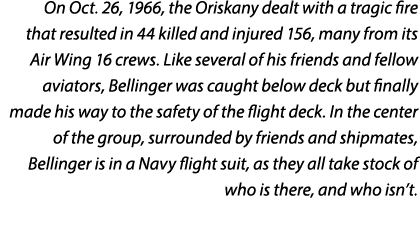

The book begins with a surprisingly highly-detailed description of early-century programs of funding and constructing a small fleet of coal-carrying colliers because the U.S. fleet did not want to defend British support of bringing coal to American ships, drawing the “Stars and Stripes” into areas far from U.S. ports. Indeed, to say the first U.S. collier would become the first U.S. aircraft carrier following Britain’s initial success in WWI was to ignore what became a major program to design and finally produce a bona fide, if initially limited air-capable ship whose main weapon was, after all, equally capable of being launched and recovered for offensive missions against an enemy target.

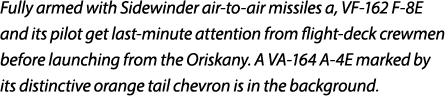

It is also surprising how active the collier USS Jupiter (AC 3) was before she was decommissioned in 1920 to begin her transition to her new career as America’s first true aircraft carrier, making several deployments to supply the fleet with coal wherever it was needed.

The discussion period about using the Jupiter as the ship to be changed into a carrier was long and complicated, and a wonder any conclusion was reached at all. At one point, thoughts turned to using it as a seaplane carrier—which at the time meant flying boats, which was usually where U.S. Navy expertise lay.

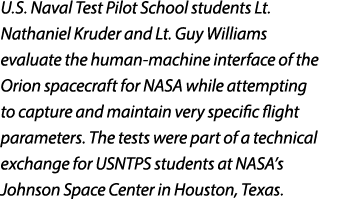

Various personalities make their appearance early in their careers such as, John Towers, Cmdr. Husband E. Kimmel (later rear admiral and commanding officer of the fleet at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese made their surprise attack on Dec. 7, 1941), and Brigadier Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell, who would be in a few years, better known for his sometimes-brash concepts about the future of Army aviation versus Navy ships, and later his court martial. His Martin bombers sunk the WWI German battleship Ostfriesland on July 21, 1921, during a demonstration mission when the ship was anchored offshore.

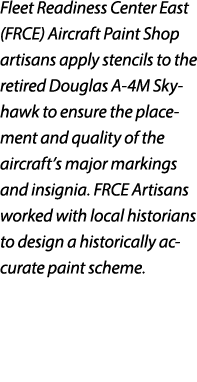

Winkler’s research and ability to absorb all he had learned is quickly apparent from the first pages. The book details the Jupiter’s busy early years and the equally busy years she and her crew endured to decide to convert “the covered wagon,” as she was affectionately known, after her conversion as the Langley, and to ferret out their “new” ship’s little-known personality, capabilities and drawbacks.

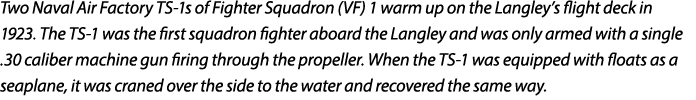

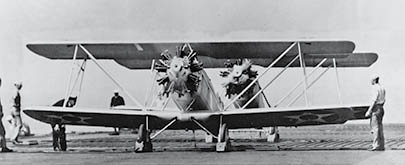

Early developments and operations on the flight deck with the cadre of early naval aviators are fascinating reading as are the first Navy carrier aircraft, such as the first operations of the Naval Aircraft Factory (NAF) PT (Patrol Torpedo) “seadrome,” a briefly produced torpedo-carrying aircraft, a hodge-podge collection of other aircraft’s parts. It was produced as a floatplane as well as a wheeled land plane in the fashion of the time, yet the author notes it “roared down the deck,” which is hardly within the limited capabilities of the WWI era early carrier types.

There have only been a very few book-length accounts dealing with the Navy’s carriers of early decades of deployments and accompanying aircraft and the new flight rules and procedures of their unique and often highly dangerous, yet important atmosphere, which quickly became the crown of national defense and diplomacy.

The Langley moved back and forth from Norfolk, Virginia, to Washington, D.C., displaying for the public, politicians and senior Navy people. While the visiting IJN captain could have been Isoroku Yamamoto, the planner of the Pearl Harbor raid on December 7, 1941, which thrust the U.S. into the war, and who had spent time in the U.S., at Harvard, and who was fluent in English, and who understood Americans well enough to be concerned what the raid might result in firming American resolve, he had actually returned to Japan by this time. The visiting Japanese captain was someone else, who was never named in the Langley’s deck log.

Winkler’s account constantly amazes me: the original collier Jupiter had a well-defined career, then it became the first U.S. carrier alternating between that of an active busy sea-borne experiment, followed by part of its nation’s growing defense. It took on growing numbers of aircraft, each with a specific purpose and mission, lasting and somewhat proudly. It sadly went into harm’s way to meet its end in combat against a tough, highly capable enemy whose many faceted operations had learned the trade and skills by closely watching how the American carrier crews had developed their new trade and mission. I will note that following chronology the various fleet exercises in which the Langley participated in was somewhat difficult because the author did not always indicate the year.

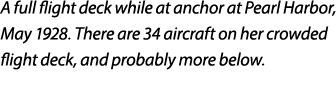

The year 1924 was a time of moving, shuttling back and forth along the Atlantic coast participating in several exercises to display the capabilities of its air groups while dealing with its flight deck’s position of the ship’s smoke stacks, a concern that remains even in today’s modern designs in different ways, creating air burbles that occasionally interfere with the safety of daily aircraft approaches.

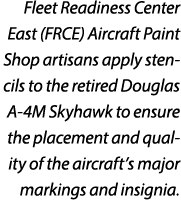

By late 1924, the Langley made its long-scheduled trip to San Diego to join the Pacific Fleet, bringing new aircraft and their crews. Oddly enough, the naval exercises of the period would often pit U.S. forces against those of Japan. It was also definitely a time of developing and training for the cadre of young newly-winged naval aviators as well as the ships’ companies, as well as bringing more and new aircraft to replace the older and rapidly aging aircraft that had first served as the Langley’s initial air groups for newer, stronger, more powerful aircraft that could dive straight down over a target and deliver a more accurate strafing run. Vought’s UO-1 “fighter” was soon replaced by the VE-7, also from Vought, when the UO-1 proved unsatisfactory. Winkler’s research and resulting narrative delivers occasionally esoteric but very interesting often little-known information that make his biography of this country’s first aircraft carrier much more than simply another account of another flattop which also makes it an important and unexpected companion to the recently published (also by the Naval Institute Press, which we just reviewed in the Winter 2024 issue) biography of Eugene Ely, who it might be said started the entire concept of an aircraft launching from and recovering aboard an American warship.

The book even gives details of Cmdr. Frank W. “Spig” Wead’s storied career as portrayed in the 1957 John Ford-directed film “Wings of Eagles.” John Wayne plays the title role of this pilot-turned-screenwriter to tell the story of Naval Aviation from the beginning through WWII. The Langley’s story appears in the early periods shown in the film. A few of the other actors who appear in various roles that today’s enthusiasts might recognize are Walter Brennan, Ken Curtis (known as Festus in the long-running TV “Gunsmoke” western series), and veteran western star Ward Bond of TV’s “Wagon Train” fame.

Winkler keeps a tremendous number of details together, yet in entertaining chronological developmental sequence throughout the narrative—not an easy thing for an historian and author. However, he is up to the demanding challenge. The between-wars narrative covers the Langley’s busy schedule of encounters with the fleet, including its new aircraft carriers, mainly the Lexington (CV 2) and Saratoga (CV 3), which would join the force to play an initially major part in the early Pacific war after Pearl Harbor.

Great Britain did have several carriers and its own naval aircraft that saw considerable pre-war service. During the war, the British made great use of a mix of their own and several American-made aircraft such as the Grumman F4F Wildcat (which they called the Martlet), and later on, the Vought F4U Corsair, Grumman F6F Hellcat and TBM Avenger. France had a single aircraft carrier, the Bearn, the only one France produced until after WWII. Converted from an unfinished battleship, the Bearn entered service in 1928, but was taken out of service in mid-1942 to ensure she was not used against the Allies. Her aircraft consisted mainly of French-manufactured types, but did include a squadron of Vought V-165Fs, exports of the American SB2U Vindicator dive bomber, whose main claim to fame came when they were flown by Marine Corps crews in the climactic Battle of Midway in June 1942.

France was quickly overwhelmed by Germany in June 1940, and most of its Navy ships and aircraft were quickly assimilated into a single unit named for Vichy and for a time fought alongside the Nazi Blitzkrieg—their aircraft colorfully marked in yellow-and-red stripes—for approximately 1941-42, especially during Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942. Strange, but although the Langley was busy throughout the 1920s and 1930s, and her crews came and went, the book’s narrative seems peaceful with little concern with events that were building toward the cataclysm of World War II.

On a personal note, the author references then-Lt. (later Rear Adm.) Rufus Fairchild Zogbaum Jr., (1879-1956), who at the time was serving as the carrier’s “gun boss,” or head of the ship’s weapons department, and his career ended with his promotion to two-star rank of rear admiral, as well as his achieving a naval aviator’s wings of gold. He also notes his being the son of noted illustrator Rufus Fairchild Zogbaum (1849-1925), whose magazine work in the 19th century paralleled that of western artist Frederick Remington and other major illustrators of the period (I graduated in 1967 from the Rhode Island School of Design’s illustration department but admittedly, I never showed capabilities that even approached those of the senior Zogbaum).

I would have been interested to see how talented his son—a Navy pilot and two-star admiral—might have been. As things transpired, Lt. Zogbaum had to deal with Eugene Ely who was monitoring progress of the construction of a landing platform for Ely’s early aircraft, which was being built right over the CO’s quarters, which did not please then-captain-later rear admiral Charles F. Pond at all; he complained of the noise.

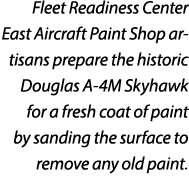

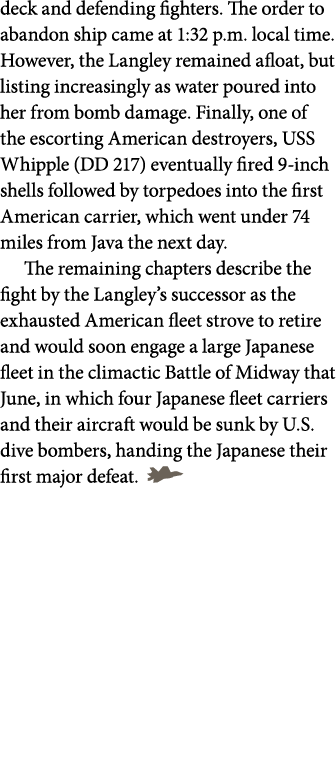

The decade of the 1930s was filled with exercises and dry-dock maintenance, keeping the old ship in as best shape as possible. In 1937, in another drastic shape and mission change, the now-aging carrier was made a seaplane tender (now AV 3), which reduced her flight deck by at least 25 percent as she supported PBY Catalinas that patrolled areas of concern, especially with apparent Japanese warlike intentions becoming clearer, with increased action in China on the ground and in the air, often by the use of IJN carrier planes involved, as well as Southeast Asia that would turn out to be much more important 20 years later as American forces entered yet another war—Vietnam.

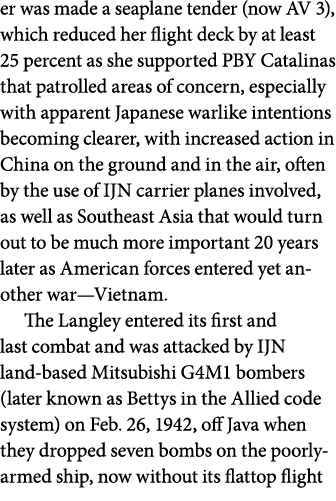

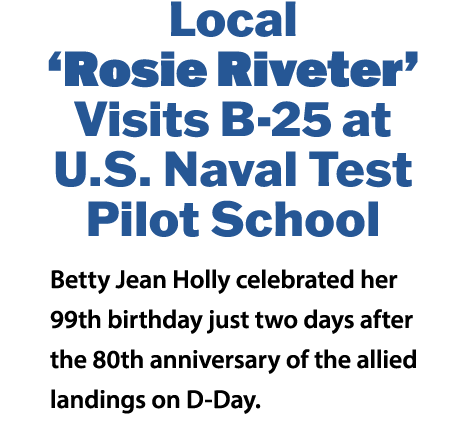

The Langley entered its first and last combat and was attacked by IJN land-based Mitsubishi G4M1 bombers (later known as Bettys in the Allied code system) on Feb. 26, 1942, off Java when they dropped seven bombs on the poorly-armed ship, now without its flattop flight deck and defending fighters. The order to abandon ship came at 1:32 p.m. local time. However, the Langley remained afloat, but listing increasingly as water poured into her from bomb damage. Finally, one of the escorting American destroyers, USS Whipple (DD 217) eventually fired 9-inch shells followed by torpedoes into the first American carrier, which went under 74 miles from Java the next day.

The remaining chapters describe the fight by the Langley’s successor as the exhausted American fleet strove to retire and would soon engage a large Japanese fleet in the climactic Battle of Midway that June, in which four Japanese fleet carriers and their aircraft would be sunk by U.S. dive bombers, handing the Japanese their first major defeat.

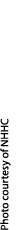

![[YOUR IMAGE HERE]](assets/images/item_19730.jpg)

![[YOUR IMAGE HERE]](assets/images/item_22835.png)

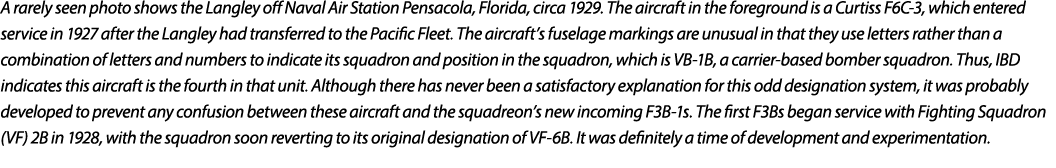

![[YOUR IMAGE HERE]](assets/images/item_19766.jpg)

![[YOUR IMAGE HERE]](assets/images/item_22843.png)

![[YOUR IMAGE HERE]](assets/images/item_19797.jpg)

![[YOUR IMAGE HERE]](assets/images/item_22848.png)

![[YOUR IMAGE HERE]](assets/images/item_19760.jpg)

![[YOUR IMAGE HERE]](assets/images/item_22839.png)

![fight’ spirit between the ship’s crew and the PSNS & [Intermediate Maintenance Facility] workforce,” said Steven Pugh...](assets/images/item_10010.png)

![[valve bowl assembly],” Castro said. “We were told basically, ‘Good luck. If you get it, good on you guys. If you don...](assets/images/item_27518.png)